Capturing Ancient Light.

I can talk, at length about astronomy, telescopes and photography - so keeping this blog short, is going to take considerable effort on my part! I shall try my best not to tangent you in to black holes and neutron stars!

A section of the Heart Nebula (IC 1805), A region rich with dust, creating light year long structures.

As a kid (as with all children) I loved exploring, and learning about the world around me - its that interest in the world that led me to discover the sciences and become fascinated with dinosaurs, space and the natural world.

As I got older the love for science and technical things continued, though I’d added an interest in art and photography with trips to galleries and taking photos from an early age on my compact 35mm film camera. (A Ricoh YF-20, which I still have, box and all!)

Photography has obviously become core to me, but that love of science and exploration has shaped much of my life. That yearning for exploration turned in to years dedicated to travelling around the world, but also a constant desire to see what’s “out there”.

It would be around late 2010, early 2011 when I saw a photograph of the surface of the Moon, and my reaction was “What? You can do that? How big is the lens?!!”

I fell down a rabbit hole of research, and by the time the end of 2011 had come around, I had discovered you can use a telescope like a camera lens and I’d made my mind up - I was going to purchase a telescope, the Meade LX90 8” SCT.

My Meade LX90 - A beast of a scope for the Moon, Planets and distant galaxies. In this photo it’s been de-forked and put on an GEM mount, which made life a lot easier.

The Meade LX90 is a beast of a scope, fork mounted, and Alt-Az orientation - in hindsight, I should have done more research, because if you know anything about astrophotography, those words made you wince!

Upon it’s arrival, I fell in love - this was going to be the start of a steep learning curve and a life long passion. This hobby blends technical challenges, science and art together.

A basic principle of photography is focal length - this is measured in “mm”. Without getting to into the weeds on this, the smaller the number the wider the field of view and will capture more of what’s in front of you, the bigger the number, the narrower the field of view and the more “zoom” you get.

A landscape photographer might use a 20mm lens, a wildlife photographer might use a 400mm lens for example. Some camera lenses in the 400-600mm range are perfectly good at getting a photo of the Moon, my telescope however is the equivalent of a 2032mm lens!

This focal length allows me to see mountains and craters on the Moon, cliffs and plateaus, you can see the very shadows cast by the mountains and crater edges, and the first time I saw the Moon in that light, I knew, to my core, that this was something I’d do forever.

This view never fails to amaze me, but before you ask, no you can’t see the Apollo landers, they’re the size of a van, those craters are tens of kilometres across and several deep!

Now the Moon is very bright, so with a little effort and an adapter I was able to plug in my camera and snap some photos, the results where amateurish, but immediately gratifying and I’d soon pick my next target - Jupiter!

I told the camera to take a shot, and …oh dear, it’s a blurry blob, that resembles almost nothing. I’ve got some learning to do.

…I mean you can sorta see it right?

I got better! The moon Io casts a shadow!

The years pass, and I’ve run in to innumerable hiccups like the Jupiter blob situation, discovering the bane of light pollution, or learning I’d just picked the worst possible scope for taking photos of nebulae.

Turns out that a lot of things in the night sky are huge, and a telescope with that much “zoom” makes a complex process like astrophotography even harder, as it means every object takes even more photos to capture (imagine trying to take a panorama, but each photo takes hours to capture!).

So time for scope number two, a gorgeous 550mm focal length scope, suited to shooting nebulae - which in my opinion are frankly the prettiest thing in the night sky with galaxies taking second place to me!

Scope two! All the cables aren’t plugged in yet - it gets much more complex!

Now if you’ve ever tried to photograph stars with your camera on a tripod, you realise that you need a fairly long exposure to capture the faint ones, you crank the dial to 2 seconds, and get a nice shot, so you try 4 seconds, maybe 10 seconds, and soon see the stars turning in to streaks - your tripod is stable, but the Earth is spinning in space and you’re now starting to see that motion in your photos.

The effect of us spinning, shown here by stacking many shots together!

Nebulae are even fainter than the stars, so you need absurdly long exposure times to photograph them.

The longer your focal length or exposure, the worse that star trail effect gets. So how do I shoot images that are at 550-2032mm that are also made of exposures often over 10 minutes in length?

You need a mount, and a good one - one that can balance your scope, your cameras and rotates very precisely using motors to counter the spin of the Earth! Not only that, it has to be aligned perfectly, balanced to a high degree, oh and having a secondary camera helps! One that tracks a star to counter any errors you made using software that then feeds back data to the mount …yup, this stuff escalates fast and I told you I love a technical challenge.

Another issue with capturing ancient light from distant stars is light pollution. The longer you expose your camera sensor, the more light bouncing around our atmosphere from street lamps, security lights etc is captured by the sensor.

You can see this easily if you take a camera on a cloudy night and take a 10 second shot, the clouds will appear yellow in colour, because of the glow from human lights.

This light from us blocks the view of faint stars and annihilates the view of galaxies, however with many nebulae, there’s a way to get around the pollution we’ve created - filters.

M63 - The Sunflower galaxy, the pinks and reds within it’s spiral arms are nebulae, forming new stars and worlds.

Most nebulae shine in specific frequencies on the spectrum, so a filter can block out every other frequency except the one we want, and the ones we want are thankfully rare on Earth as the processes that make them occur almost exclusively in space. This effectively deletes 99.99% of human made light pollution, allowing me to see the things I want - however this adds even more complexity.

The Monkey Head Nebula - photographed from my back garden in Looe.

So that was the next expensive rabbit hole to fall down. I go from shooting with a digital SLR, to buying a specialist cooled (for reasons, that I won’t get in to) black and white CCD camera, that then captures light through multiple different filters with a secondary camera tracking the motion of the stars, all plugged in to a laptop, and I then have to blend the data from multiple filters to produce an image… yikes!

Many things in space are red, pink or purple, due to the nature of what many nebulae are made of (hydrogen gas and sulphur come out as shades of red, and oxygen blue through my filters).

The Elephant Trunk Nebula. (I see a woman with long hair walking away…)

No doubt you’ve seen fantastical shots with vivid greens, oranges, teals etc, so what gives?

From a science point of view you want to show what a nebula is made up of, and where that “stuff” is whin the object. If you show sulphur as red and hydrogen as red, it’s not going to be super clear, even with different shades. So most scientists will colour Hydrogen green, Sulphur red, and Oxygen as blue, this leads to photos that let you see the interaction of these gases easily and where they reside.

The Pac-Man nebula, the rich dust clouds giving it amazing dark regions, the centre is a strong mix of Oxygen and Hydrogen, with its outer layers having an abundance of Sulphur gas.

From a photography point of view, it becomes more “art”, you’ll choose pleasing colours to show off the subtle structures within the object, with dust and stellar winds sculpting these vast clouds of gas that form new worlds, stars and more!

So the images I produce, whilst real, are not always their true colours, and this is where the art comes in!

Astronomy is a blend of science, a complex technical challenge and a little art - there’s an inherent beauty to these things and wonder they inspire when I see them through my scope, this furthers my desire to understand what I am seeing, which feeds back in to my love of science.

Astronomy teaches me patience to, it can take a long time to get one photo of something in deep space.

Lets imagine I wish to photograph a nebula that’s faint enough to need a 10 minute exposure…

Considering all of the above, the scope needs setting up and fine tuning, the sky has to be clear of clouds, the wind not to strong to make guiding hard. Then the Moon needs to be either far away from the shot, or not about at all.

The shot will require three filters, Hydrogen, Oxygen and Sulphur (Ha, OIII and SII), so I need to photograph it three times right? Thirty minutes isn’t that long? Sure, but the longer the exposure, the more noise you get in the image, or a satellite might whiz pass giving you a streak in the image, or a cosmic ray might strike, giving you a random bright spot (…tangent warning, but that’s so cool!) So more images right?

Yup! You stack multiple images on top of each other to cancel out noise, or random events.

On average I take about 120 images for one photo, 30 in each filter and a selection of calibration photos (which I shall skip over the details about!).

120 x 10 minutes = 20 hours, which means you need multiple clear nights with good conditions to get a photo. Now imagine shooting a panorama!

The Orion nebula, with the Running Man nebula to the left. This nebula is a vast stellar nursery, full of giant young stars that burn so bright they light up the gas that formed them!

This overview also skips over other factors, like position in the sky, how dark it is (I loathe summer!), and if I can stay up until 4am taking photos, when I’ve got a wedding the next day to shoot!

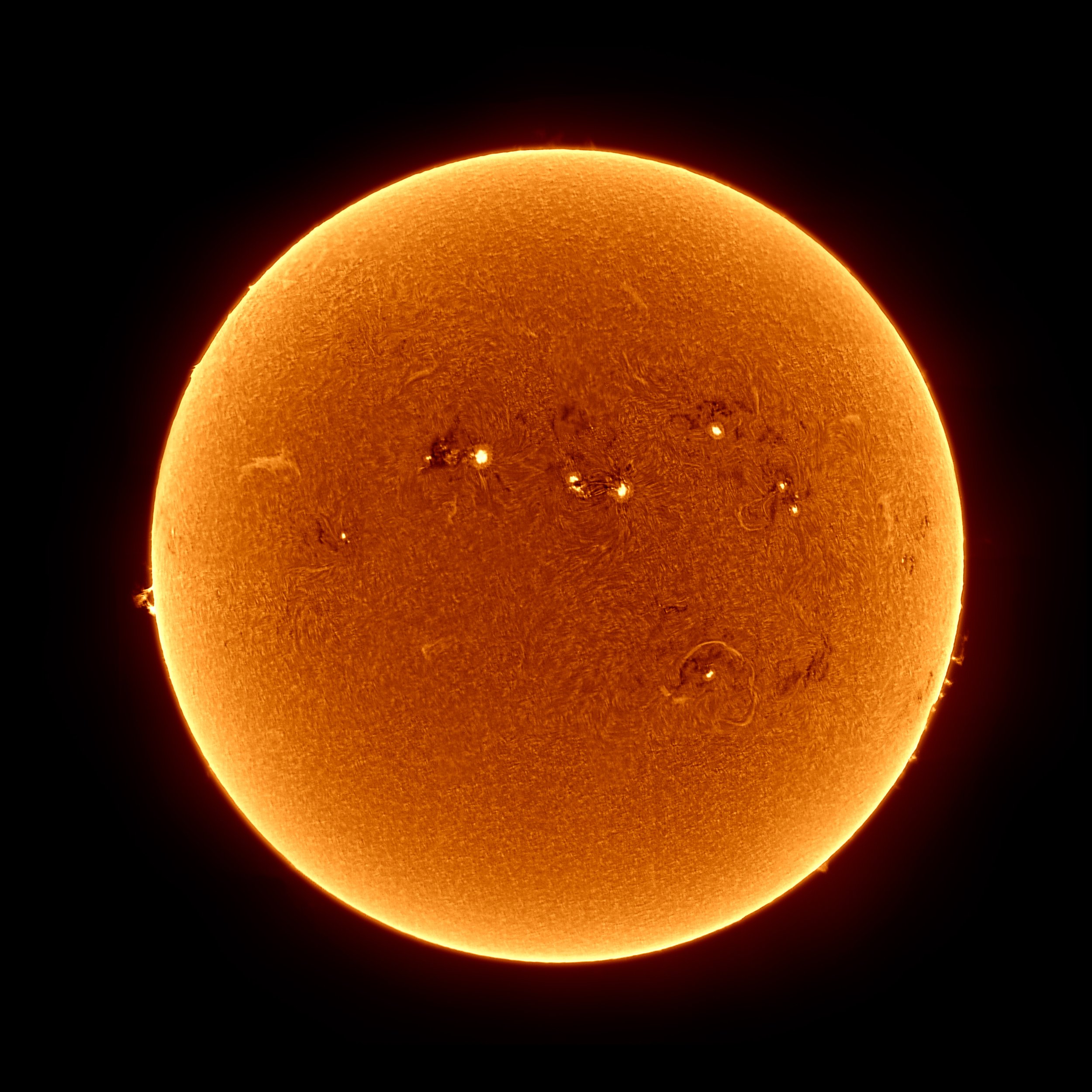

Needless to say, this is a passion of mine, and I’ve learnt an awful lot to get me to this point, yet there’s always more to learn, or a bigger scope to get, or photographing the Sun, or rare events, discovering new objects….

Of course you can photograph the surface of the Sun with very specialist equipment, but that’s a tale for another day!

One thing I will say, I am privileged to have seen the beauty out there in the universe with my own eyes, it’s vast, fascinating and humbling - I feel incredibly small when measured against it, but deeply part of something beyond the scope of anything we can imagine.

I love the fact that through the skills I’ve gained by falling in to this passion, I can share the view I get with people, indeed if anyone ever asks to look through my scope, I am always “you first”, because that moment when you see the rings of Saturn for the first time, is truly, utterly magical, and that magic has not left me.

The view I get of Saturn - never fails to amaze me.

…this blog was hard to write, not because of the subject, but because it took all my will power to not tangent in to a million side notes.

If you enjoyed the photos, check out more here!